Bonanza Peak, west side, Jan 2012. The objective buttress is in the center of the photo.

Bonanza Peak, west side, Jan 2012. The objective buttress is in the center of the photo.

|

• INTRODUCTION •

In July 2012, I joined pilot/aerial photographer John Scurlock on a flight to check out a malfunctioning seismograph on Glacier Peak. On the way back to the airstrip in Concrete, we flew at eye-level past the towering western walls of Bonanza Peak. As I snapped a few shots of a 2300-ft nearly-vertical buttress leading directly up to the SW Peak, John commented: "That's one of the grand buttresses of the North Cascades. And you know, I'm not sure if it's been climbed."

View from S-SW.

|

View from SW.

|

View from W.

|

Intrigued, I began to do some research about the climbing history of Bonanza's west side. First I went to my

Cascade Alpine Guide (CAG). Sure enough, under the Southwest Peak of Bonanza was a brief description of a 22-pitch route called the "Soviet Route" aka "North Face of Southwest Peak." The first ascent had been done in September 1975 by a Soviet team. It was a Grade V route. In my searching, I could find no record of the route being climbed since the first ascent.

(Update: After I posted this trip report under the assumption that we had done the second ascent, it prompted a response that there actually had been a second ascent in 1977 by Dave Stutzman and Bob Plumb. Bob Plumb writes: "[We] did the second assent of this route in 1977 as a training climb before we went to Alaska and climbed the North Face of Devils Thumb. We did it in a day and I remember it being really loose with some 5.10." So our climb in 2012 was likely the third ascent of the route. Unless another pre-internet-era ascent party comes out of the woodwork....)

The CAG provided references to three articles written soon after the first ascent: one in

Mountaineer (1975), one in

American Alpine Journal (1976), and another in

Off Belay (1976)

. I thought it would be interesting to get ahold of these articles. The article from the 1976

American Alpine Journal was easiest to find, since it was online in the AAC database. Titled "A Soviet First Ascent in the North Cascades" and written by Alex Bertulis who joined the four-member Soviet team on the climb, the article gave a fascinating account of the story behind and experiences during the first ascent. The text of the article is given below. Note that the difficulty ratings noted in the article — F8, F9, F10 — are about equivalent, respectively, to 5.8, 5.9, 5.10a/b (nice climbing grade conversion table

here).

Article published in the American Alpine Journal, 1976, pgs 340-344:

A Soviet First Ascent in the North Cascades

by Alex Bertulis

. . . when tied to the same rope, there

is more than one bond that transcends

language, culture and ideology.

When the Soviet team arrived in Seattle, we met them, for the first time, during a luncheon in the Plaza Hotel. I arrived a little late and at first glance I could not be sure which of the fifteen persons at the table were the foreigners. A series of introductions by Pete Schoening and a round of handshakes quickly acquainted me with the Soviet guests and some of the Northwest hosts.

About a week later, after a Northwest tour that included an ascent of Mount Rainier, water skiing on Lake Washington and a visit through 37 departments of the local Sears and Roebuck store, I was advised that, as a finale, our guests would be interested in a “hard first ascent” in the North Cascades, but one that involved no more approach difficulties than driving up in a car and marching off the roadway to the first pitch! Well, accessibility is not exactly what the North Cascades are famous for but upon viewing my slides of a 2300-foot, nearly vertical, buttress that was still unclimbed, the Soviets admitted that the two-hour hike to its* base would not be objectionable. *The north face of the southwest peak of Bonanza (at 9511 feet, the Cascades’ highest non-volcanic mountain).

Early in the morning of September 10, the “North Cascades team” (Vitaly Abalakov, Vladimir Shatayev, Vyacheslav “Slava” Onishchenko, Valentin “Valia” Grakovich, Anatoly “Tolia” Nepeomnyashchy, Sergei Bershov, all of the USSR and Nina Cvetkovs, Mike Helms, Jim Mitchell and I) drove over to the east side of the Cascades, sailed forty miles up Lake Chelan, drove ten more miles over an old mining road in a “wilderness taxi,” and after a three-mile hike, arrived at the “Bonanza base camp” on the north shore of Hart Lake (3935 feet) still early in the day.

After a refreshing swim in the ice-cold waters of the lake (the Soviets never lost a chance to “skinny dip” in any body of water they happen to encounter), the rest of the afternoon was spent sorting out food, gear and tactics for the climb. American freeze-dried food, nylon down gear and “rip-stop” nylon tents impressed the Soviets very much. The Soviet hardware collection included many innovative designs (mostly by Abalakov) for both rock and ice climbing. Most of their pitons were titanium, which combines the strength of steel and the light weight of aluminum. The drawback of titanium pitons is that they deform quicker, during repeated use, than pitons of chrome-molybdenum steel.

Starting early the next morning we ascended the steep rock and heather terraces to the 7100-foot pass between North Star and Bonanza Peak in about two-and-a-half hours. It was a perfect autumn day. As we reached the pass the north buttress of the southwest peak of Bonanza came into close view. Slava studied it for a while then, gesturing, asked me where the route was? There was no apparent fault system that indicated that the buttress would even “go.” I responded, “The route is where you make it. I wish you luck!” I gave them one more opportunity to make it a team of four (Onishchenko, Bershov, Grakovich and Nepeomnyashchy)* (*Shatayev remained in camp with fever. Abalakov explored the North Cascades via its beautiful valleys.) but they all insisted that I must climb with them.

As we roped up at the base of the buttress, I was startled to see Slava and Sergei put on petit galoshes that stretched tight over their bare feet! Sergei took the first lead up a narrow chimney and proceeded up the broad face above while Slava belayed. Tolia informed me that I would be on the end of his rope with the privilege of cleaning all the pitches. Valia tied a prussik near the middle of the rope and often climbed simultaneously without a real belay, even over F9 terrain!

As we proceeded upwards, the climbing remained demanding (F7-F9). Sergei and Slava were well ahead and could be seen maneuvering under some major overhanging headwalls. Tolia often remarked to me that he would certainly prefer his gloshes now instead of the conventional climbing boots he had on. Valia, a very strong climber who did not enjoy following as much as he does leading, started shouting up at his compatriots that in his opinion they should be attacking the headwalls directly (with aid) and be done with it! I (politely) squelched his vocal efforts and said, “Give them a chance; they may see something we cannot.” My words were prophetic. Sergei and Slava, far from encountering insurmountable impasses, reached a sloping ramp that cut diagonally across the crest of the buttress (from east to west) circumventing two of the headwalls. It was an unexpected and important key to the route!

The next few leads involved some of the hardest that I have ever witnessed under alpine conditions: three consecutive pitches of F10 and sustained F8 and F9. As we reached our bivouac ledge, I learned that Sergei did almost all the leading. His stature as USSR rock-climbing (speed) champion is well earned, I thought.

The setting sun silhouetted the mountains of the Olympics and Vancouver Island while hot food and liquids were shared. Songs, jokes and stories abounded late into the night. The spirit was contagious and our language differences presented no barrier. We were all slipping off into sleep when the resident “snaffle hound” (Pika) started scavenging through our utensils for dinner leftovers. Anchored loosely to some pitons I remained still and semi-awake as the familiar commotion continued close by. Suddenly, I felt this “monster” running over me! When his feet hit my face I jumped up yelling and cursing. My Soviet buddies thought I had been “attacked by a bear” and my description of the beast supported that impression. A “bear hunt” failed to produce a quarry. I lay back down to sleep with my hammer at hand, just in case. More jokes, at my expense, kept us awake a while longer.

By late the following morning we had surmounted the final headwalls of the buttress and were jubilating on the summit. I asked Slava, who had done some of Europe’s hardest climbs, what his impression of the route was? He said that “some of the climbing was very hard and some not so hard, but if the weather had become bad it would have been very difficult to escape the face.” Having experienced September blizzards in the North Cascades, our predicament on the face would have been unpleasant, indeed, if the weather had broken. A quick descent over the numerous glaciers and cliffs of Bonanza’s 5000-foot south face brought us hot and thirsty to Base Camp and another, most refreshing swim in Hart Lake.

* * *

In cleaning the many pitches (22) I was impressed at the Soviet’s expert approach to “clean climbing.” During this climb over a hundred chocks, nuts, wedges, etc. were placed for protection whereas only six (knifeblade) pitons were used. Two (titanium) pitons were placed in such difficult (desperate?) positions that I was unable to remove them (as future parties will probably be happy to discover).

By far the most impressive item that the Soviets had was the “Abalakov Cam.” This most effective anchor is as ingenious in design as it is simple to use. Almost every belay on this climb was safely and quickly secured by one “Abalakov” rather than several conventional nut and chock placements. This cam is easy to make and Mr. Abalakov expressed the hope that it would be produced in this country without patent restrictions.

Summary of Statistics:

Area: Cascade Mountains, Washington.

New Route: North Face of the southwest Peak of Bonanza, 9511 feet, September 12, 1975, NCCS VI, F 10.

Personnel : Vyacheslav Onishchenko, Valentin Grakovich, Anatoly Nepeomnyashchy, Sergei Bershov, USSR and Alex Bertulis, USA

Tracking down the 1975/6 articles from

Mountaineer and

Off Belay was a bit more of a challenge. I enlisted my friend Roger Beckett—thanks Roger!—to help out. He found them

in the George Martin Mountaineering Collection at the Olympic College Library in Bremerton. These articles were also written by Alex Bertulis, so they were very similar to the

AAJ article; even so, each provided a few extra tidbits of useful route and background information.

It was pretty clear that the route described in the CAG and the articles did indeed ascend the 2300-ft buttress in question. However, It seemed a bit odd to call this route a "North Face" when the buttress in question was clearly a west-facing buttress (I would have expected the route to be called "West Buttress"; this misnomer was also the cause of John Scurlock's comment that the "west buttress" had not been climbed). Perhaps the naming had something to do with the fact that "North Face" attracts a certain mystique of difficulty and ruggedness; so when the route line tended towards the north side of the crest, it was coined the "North Face."

Whatever the name, the 2300-ft buttress had captured my attention. It is the steepest and tallest wall on the complex Bonanza massif, and a rival in size and difficulty to many of the biggest faces in the Cascades. I emailed my friend Dan Aylward to see if I could pique his interest in possibly

attempting to climb it later that summer, first ascent or not. Dan was immediately intrigued, as was his friend Chad Kellogg. The three of us began making plans to climb the buttress.

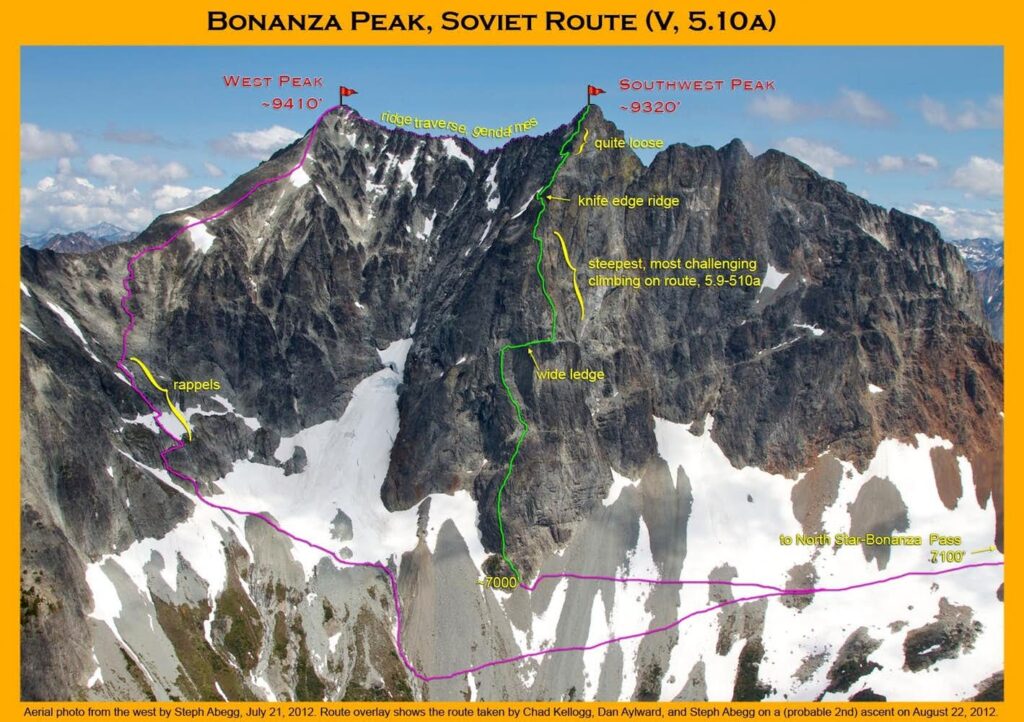

Our route information was meager—especially considering this was a 22-pitch 2300-ft route!—being limited to the brief route description in the CAG, anecdotes in the 1975/6 articles, and high-resolution aerial photos. Essentially, we knew there was a possible way up the buttress but other than that we were mostly on our own to find it. But heading into the unknown was part of the allure of this route. It was bound to be an adventure.

And an adventure it was! The following page gives a route overlay, map, and several photos (and helmetcam video!) with detailed descriptions.

But first, a few notes on gear, etc:

- As a team of three, we climbed on a double rope system with the two followers being belayed up at the same time, separated by 10-30'. This worked out well and did not take much more time than climbing as a party of two, besides for a little more rope management attention at the belays. Having an extra person to talk to and being able to switch on and off duty at the belays made the climb seem much more relaxing too.

-

Dan and Chad led in blocks, while I took the comfy position of follower for the entire route.

- With full 200' pitches and simulclimbing a few sections, we climbed the route in 14 pitches and 4 belay moves on easier terrain—for comparison, the Soviet party noted 22 pitches, probably due to shorter ropes and passive protection only (i.e. no cams, which came onto the scene in 1978).

- We had and used a lot of small cams and nuts. Interestingly enough, a miscommunication had caused the #3 and #4 cams to be left at home. Fortunately it turned out they were not needed. The blue Alien was the most-used piece.

- We agreed that overall the route is correctly described as the Grade

V, 5.9-5.10a given in the CAG. The hard pitches were mainly in the middle half of the route (particularly in the third

quarter of the route), while much of the other climbing on the route was in the 5.6-5.8 range. Overall the route was easier than we had expected.

- I climbed about half of the route in my approach shoes, putting on my rock shoes for the steeper and more delicate pitches in the middle half of the route.

- The rock was typical of the North Cascades, with some sections of extreme looseness (particularly the red rock!) and other sections of enjoyable solidness. Fortunately, the difficult pitches had relatively good rock.

- It took us 12 hours to climb the buttress from its base to the SW Peak. Camp-to-camp was 21.5 hours.

- We had a couple of helmetcams with us which were a lot of fun and gave some unique footage of climbing in action.

- It was interesting how the route pretty much creates itself. We did not put much effort into following the vague route descriptions we had, yet we ended up following pretty much the route line as the Soviets, evidenced by the landmarks (headwalls, horizontal ledge, cave belay, left/right sides) we came upon.

- We did not see any sign of other people having climbed the route (no

slings, pitons, nuts, etc.). So unless we hear otherwise

we will assume this was the third ascent of the route (the second having been done in 1977 as mentioned above).

• ITINERARY •

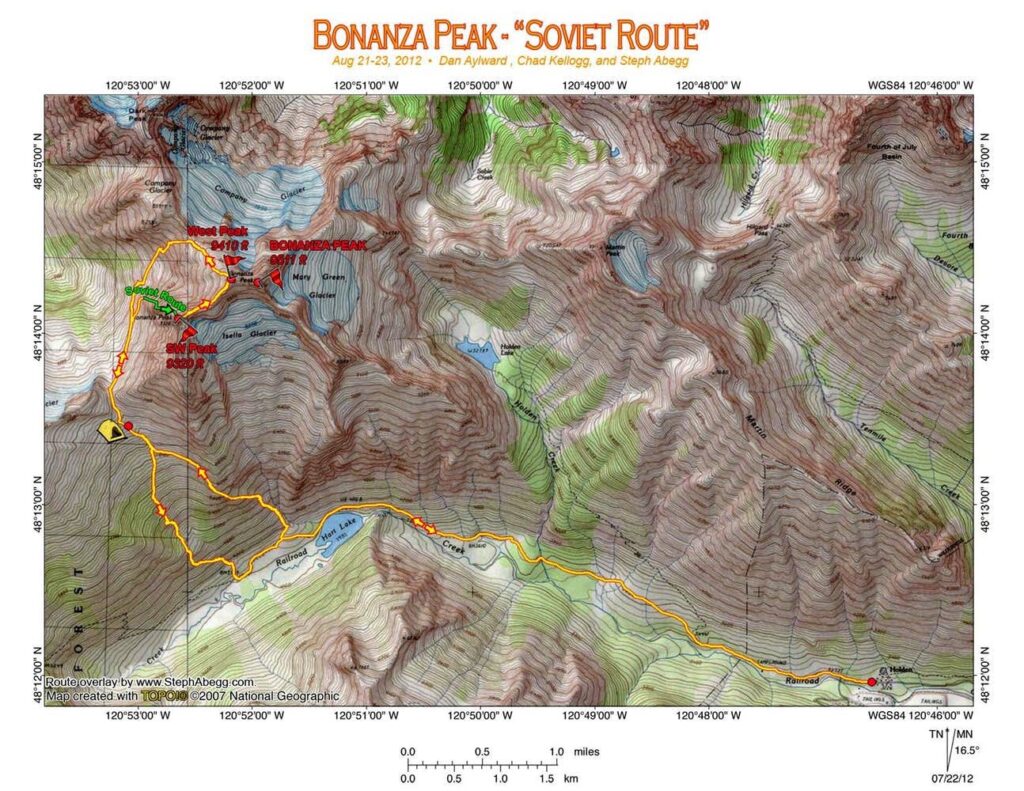

- Day 1: Catch 8:30am Lady of the Lake ferry from Lake Chelan Boat Company dock in Chelan, arrive in Lucerne at 12:00pm. Take 13-mile bus ride to Holden Village (3262 ft). Hike 3.5 miles along Railroad Creek Trail to Hart Lake (3956 ft). From lake, ascend to just below 7100 ft pass between Bonanza and North Star Mtn.

- Day 2: Traverse talus to the base of the buttress. Climb the "Soviet Route" to the SW summit of Bonanza (3rd known ascent). Traverse the ridge from the SW Peak to the W Peak. Descend the NW side of Bonanza. Arrive back at camp 21.5 hours after leaving. Eat and sleep.

- Day 3: Hike out to Holden. Catch bus to Lucerne. Catch 2:30pm ferry from Lucerne to Chelan. Drive home. Eat. Sleep.

• PHOTOS / VIDEOS •

Day 1: Boat/hike in.

|

The standard approach to Bonanza is from Holden, which is accessible only by a ferry to Lucerne and then a bus ride from there. In the summer, the Lady of the Lake ferry makes a daily trip from Chelan to Lucerne; the ferry leaves Chelan at 8:30am and takes about four hours to get to Lucerne. It costs $34.50 per person (round trip fare). Also it is $7/night parking near the boat dock in Chelan.

|

|

We had with us some high-resolution aerial photos that I had taken in July (loaded on Dan's iPhone which we brought along on the climb). Although we relied more on our eyes and surroundings to determine our route during the climb, the aerial photos were useful to have in order to scope out various route possibilities and to see what lay ahead.

|

|

There was a bus waiting at the ferry dock in Lucerne to drive people (mostly Holden guests) the 13 miles to Holden. $15 round trip fare per hiker.

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

Beginning the hike. From Holden, we hiked 3.5 miles along Railroad Creek trail to Hart Lake. (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

Taking a dip in Hart Lake, although not quite in skinny-dipping Soviet style.

|

|

From Hart Lake, we ascended the rock and heather terraces to the west (left) of the waterfalls/cliffs. It took about 3 hours and 3000 ft of elevation gain to get from the lake to where we set up our camp just south of the 7100' pass between North Star Mtn and Bonanza.

|

|

There are plenty of flat and parklike camping opportunities just south of the 7100' pass between North Star Mtn and Bonanza. Water too!

By the time we arrived at camp, the clouds were bearing down and it became quite windy. We started to wonder what to make of our supposed good weather forecast...

|

Day 2: Climb Soviet Route on Bonanza.

|

At 5am we were crossing the endless talus to the base of the buttress. It took a little less than 1 hour to get from camp to the base of the buttress. The windy and cloudy morning had inspired coffee over speed so we were 40 minutes behind our goal to be climbing at first light.

|

|

Chad leading up Pitch 1. This seems to fit the description of where the Soviet team started upwards: from the 1976 AAJ article: "Sergei took the first lead up a narrow chimney and proceeded up the broad face."

|

|

The route pretty much starts at the toe of the buttress, about 60 feet above the lowest point. You could probably traverse in from higher ground, but what would be the fun in that?

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

Steph doing some steep face climbing on the 4th pitch. This was the hardest part of the route so far, perhaps 5.9/10a for a few delicate moves. I was bemoaning the fact I had to put on my rock shoes after climbing the previous three pitches in my warm and comfortable approach shoes (all told, I climbed about half of the route in approach shoes, which work well for me up to 5.9). (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

Looking up at the major headwall that extends up to about halfway up the route. We climbed the left wall in this photograph (E of the headwall). The morning cloud deck adds a nice ambiance.

|

|

Dan belaying while Chad climbs upward on the walls left/E of the major headwall. For the most part, the belays on this route were comfortable and roomy, which was nice for rope management (we had 2 60m ropes) and three people.

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

About midway through the route is a major horizontal ledge that cuts across the headwall. This video shows Chad leading up towards the major horizontal ledge. (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

According to the 1976 AAJ article about the first ascent, this major horizontal ledge is the "important key" to the route: "Sergei and Slava, far

from encountering insurmountable impasses, reached a sloping ramp that

cut diagonally across the crest of the buttress (from east to west)

circumventing two of the headwalls. It was an unexpected and important

key to the route!"

Like the Soviet party, we traversed across this to the right side of the buttress.

|

|

Shadow of the mountain on the clouds above. Blue skies! By mid-morning, the clouds had burned off and we enjoyed a calm and sunny day.

|

|

After traversing the ledge to the right side of the buttress, we headed up this steep rock for a couple of pitches. As mentioned in the 1976 AAJ article ("The next few leads

involved some of the hardest that I have ever witnessed under alpine

conditions: three consecutive pitches of F10 and sustained F8 and F9") this section of the buttress was probably the most challenging and sustained climbing of the route, with a number of 5.9 moves and possibly a few 10a moves too. We were a bit disappointed not to encounter any of the original party's titanium pitons that had supposedly been left during "desperate" moments.

We eventually crossed to the buttress that continues on the right of the photograph. You cannot see it in this photo, but there is a knifed connection that allows relatively easy access to the continuing buttress.

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

Dan leading one of the steep crux pitches above the ledge. (Helmetcam footage by Chad Kellogg.) |

|

Midway through the crux pitches is a nice cave belay. This photo shows Dan Aylward leading out from the cave belay onto delicate face terrain and vertical chimneys.

|

|

Chad climbing just above the cave belay. The benefit of climbing as a team of three (with both followers climbing at the same time ) is that you can take nice up-close climbing photos!

|

|

A comfortable yet exposed belay station about 3/4 of the way up the route. Another nice thing about climbing as a group of three is you can take a nap at the belay!

|

|

Dan leading off the knifed connection to the upper summit tower, about 3/4 of the way through the route. This was easy and exposed climbing.

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

Dan took a video as he climbed the easy (albeit loose) terrain just above the knifed connection. (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

A shadow photo taken while on the exposed ridgecrest.

|

|

At the base of the final summit tower, just after the ledge where the Soviet party had bivied, we encountered an overhanging summit headwall. We climbed left and upwards. The rock here was the loosest of the route. Our mantra about Bonanza's rock: "If it's red, watch your head...."

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

The final scramble to the summit of the SW Peak. Base to summit in just under 12 hours! (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

Putting to good use a balloon found on the route, Bonanza Bill celebrates being the first (known) stuffed mountain goat to reach the summit of Bonanza's Southwest Peak.

|

|

Looking over at the West Peak (~9410 ft) and main summit (9511 ft) of Bonanza. The summit ridge of Bonanza is about a mile long in its entirety. Hmmm....it's a long way to go...can we make it there before dark?...probably not. Ideally, the plan was to traverse over and tag the true summit before heading down. However, a route description for the traverse between the two summits (described as the NE Ridge of the SW Peak in the CAG) noted 6 hours for the gendarmed and "5th class" traverse. It was already 6pm so we had only a couple of hours of daylight left. We figured we would see how long it took us to get to the West Peak (since we would descend from there) and decide how we felt about making the rest of the traverse in the dark.

|

|

While we still had daylight, we scoped our our descent. We had initially planned on descending via the Isella Glacier on the south side of the mountain, but we spotted a possible descent route on the NW side that would get us back to the easy basin we had approached that morning. This photo shows the area where we descended. Much of it was a talus downclimb until steep slabs which forced us to make two 200' rappels. Then it was just a bit more easy downclimbing to the talus below, which put us in the same talus basin we had approached that morning.

|

|

Chad traversing between the SW Peak and the W Peak. In this photo he is nearly at the W Peak. Due to all of the gendarmes to negotiate (mostly by dropping down onto 3rd/4th class ledges, once involving a short rappel), it took us nearly two hours to traverse to the W Peak.

|

|

It was a beautiful evening. This photo shows an alpenglowing Glacier Peak behind the SW Peak of Bonanza, taken from near the W Peak on the traverse between the SW Peak and W Peak. As the photo shows, there are several gendarmes to negotiate on the sharp crest.

|

|

The sun set just as we reached the West Peak.

|

|

Twilight and Earth's shadow on the main summit of Bonanza, taken from the W Peak. The CAG route description told us 4 hours from here of "loose 5th class" terrain. We had to make a decision....

|

VIDEO AT END OF PAGE

Footage of our pow-wow on the summit of the W Peak. Much as each of us wanted to reach all three of Bonanza's summits—particularly the highest summit standing 0.3 mile distant—we agreed that it would be unsafe to climb the loose and unknown 5th class terrain in the dark, especially after a long day of climbing. We tossed around the idea of bivying and making the traverse in the morning, but we were not prepared to spend the night in freezing temperatures above 9000 ft, and we were all low on water. Another consideration was being able to catch the ferry back to Chelan the next day. Given that we felt we could make a safe descent in the dark, it seemed wise to just keep moving. It was a bit disappointing, but we had to remind ourselves that we had achieved the route and summit that was our main goal, plus the W Peak as well. (Helmetcam footage by Dan Aylward.) |

|

Around 16 hours on route now: Chocolate-covered espresso bean time!

|

|

From the W Peak, we descended talus to the NW and eventually encountered the steep slabs we had seen earlier in the day when scoping our our descent route from the SW Peak. We made two 200' rappels into the dark. It's always a bit concerning to rappel into the dark abyss without knowing for sure if there will be good anchor or ledge opportunities below, but fortunately we found good options. We left a nut at the first anchor and a piton at the second. A pretty cheap descent I'd say!

After two long rappels, we hit downclimbing terrain that brought us to the talus slopes below. From there it was an endless talus traverse back under the buttress and to the North

Star-Bonanza saddle and to our camp. We arrived back at camp safe, sound, satisfied, and sleepy. It was 21.5 hours after we had left it. We had a few hours until we had to wake up and hike out to catch the ferry back to Chelan....

|

Day 3: Hike/boat out.

|

Not excited to traverse any more talus, we decided to return to the trail via a treed drainage a rib westward of the way we had ascended from the lake. This descent was pretty good, besides for a cliffband half way through (which we were able to downclimb) and some rather dense 'schwacking as we neared the valley bottom. It took us about 2h40min from camp to the trail which is comparable in time with the way we took in.

|

|

'Schwacking to the trail. Every good trip in the North Cascades involves bushwhacking at some point or another.

|

|

Even though we arrived back at camp at 2:30am after 21.5 hours on the route, we had to wake up early to hike out and catch the ferry to Chelan. As the photo shows, we made good use of the 4 hour ferry ride.

|

Dan Aylward has posted his version of our adventure here on CascadeClimbers.com. His trip report provides a lot of anecdotes and details that mine does not, so check it out!