The Picket Range is one of the most rugged areas of the North Cascades. Although the difficulty of the climbing is often moderate, the routes are committing and remote, and any mishap can turn deadly. This fact became all too real when on July 5, a climbing accident occurred on the Stoddard buttress of Mt. Terror. A stretch of bad weather worsened the situation, leading to a 5-day rescue operation, which ultimately ended in success due to a series of well-thought decisions and the dedication of the rescue team. The following report details the climbing rescue. There is a reason it's called Mt. Terror.

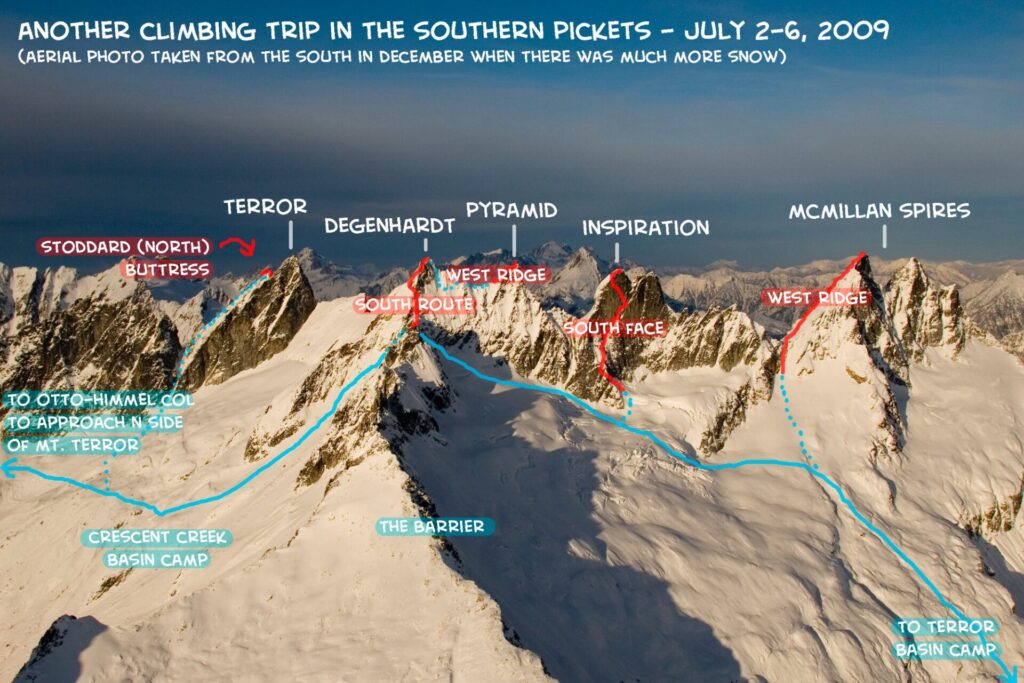

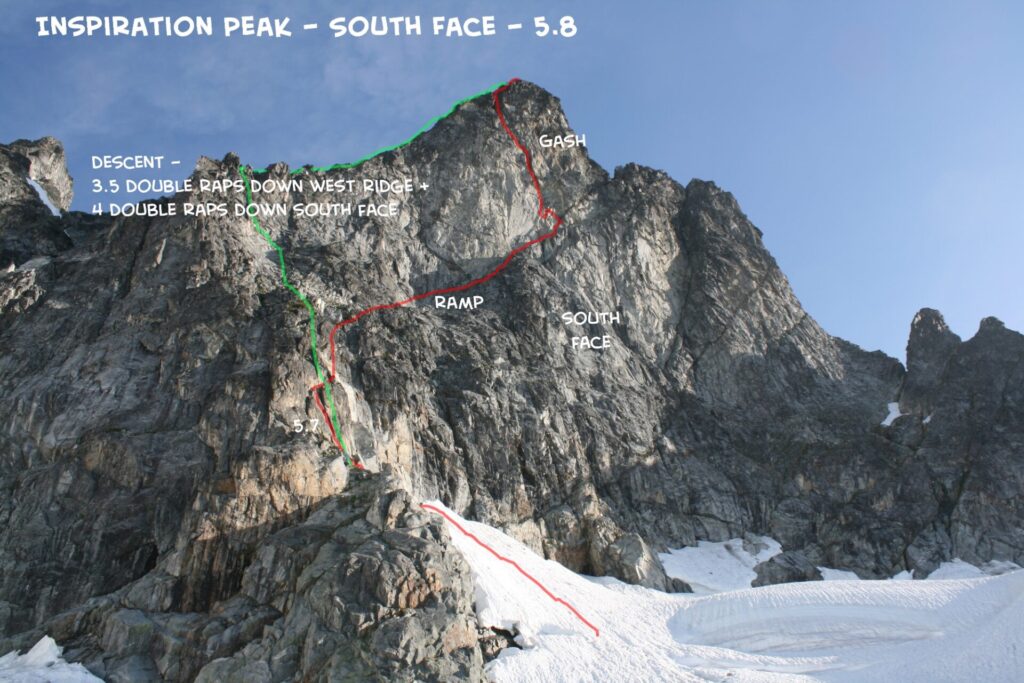

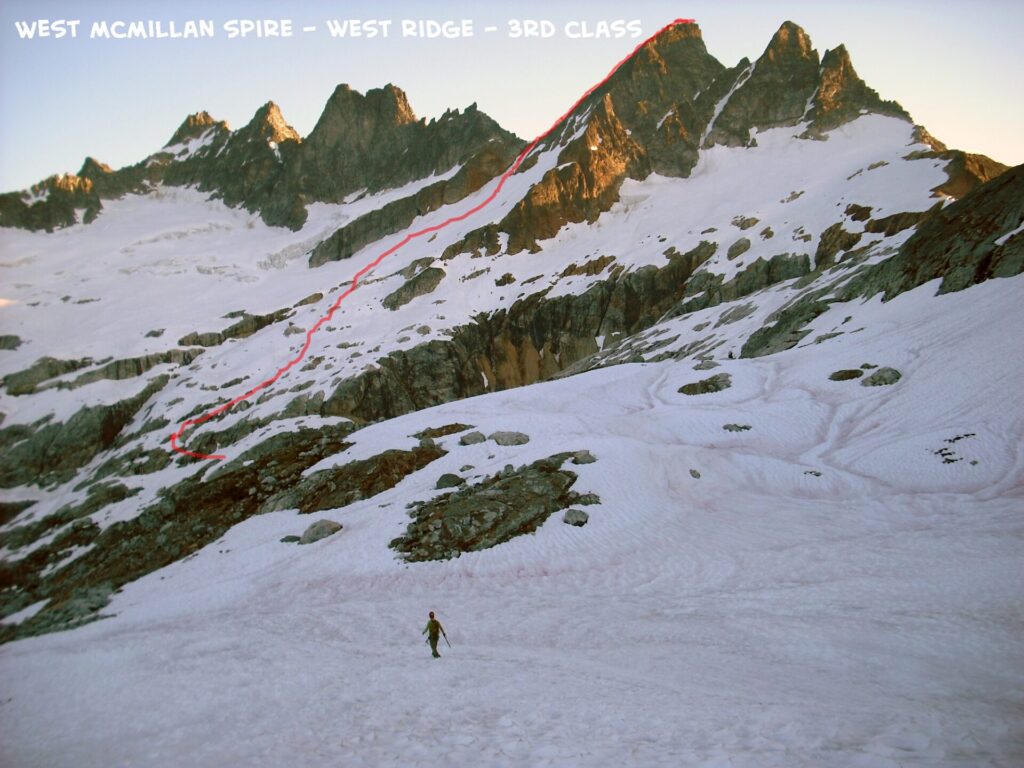

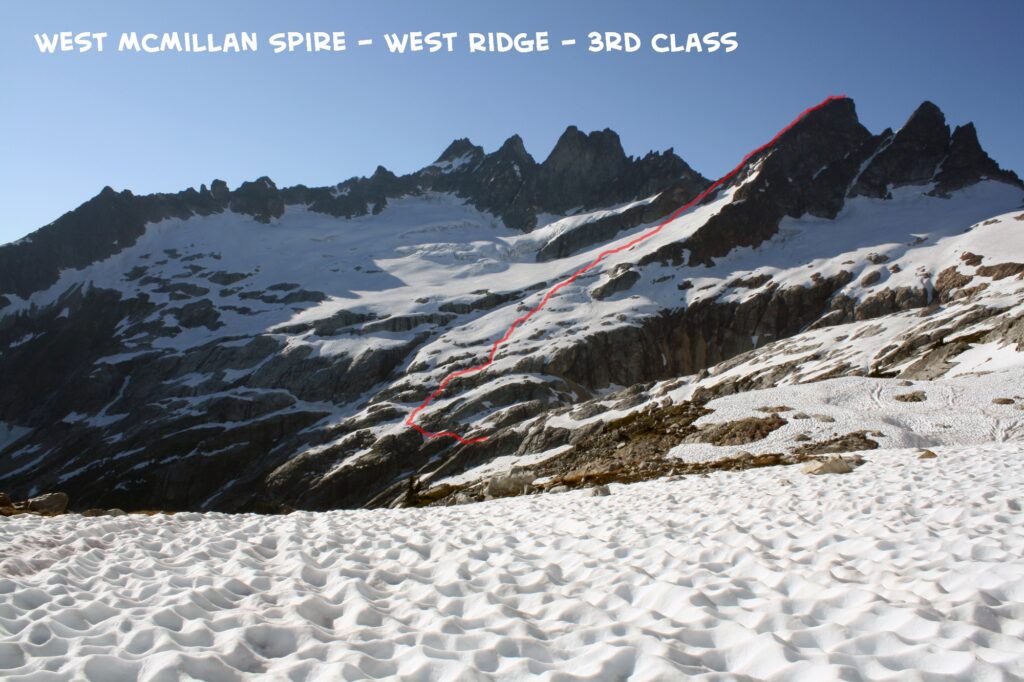

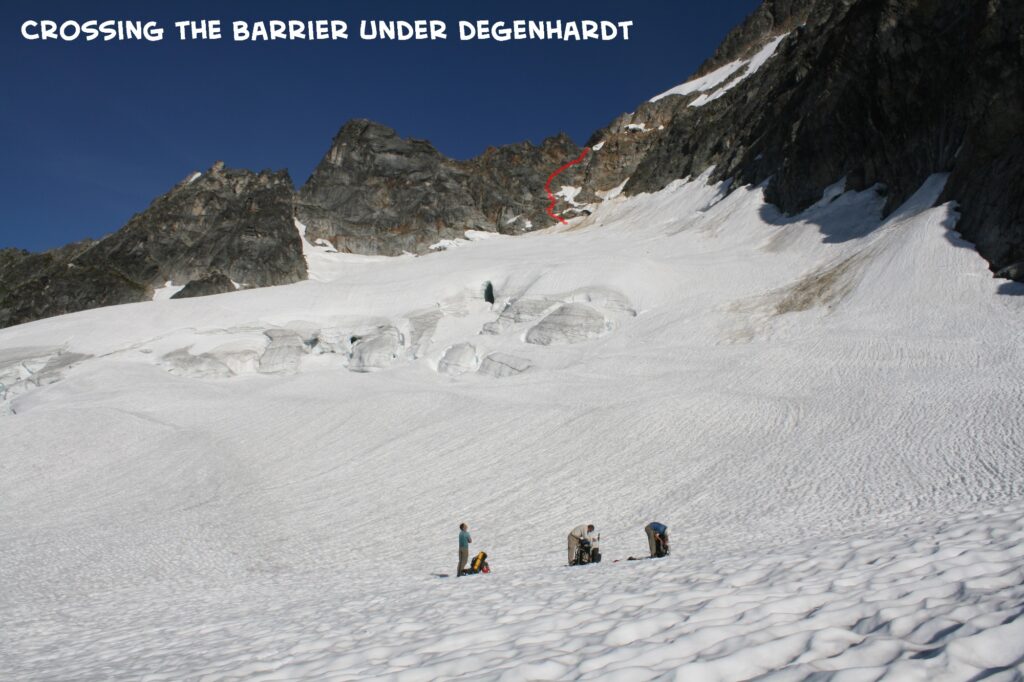

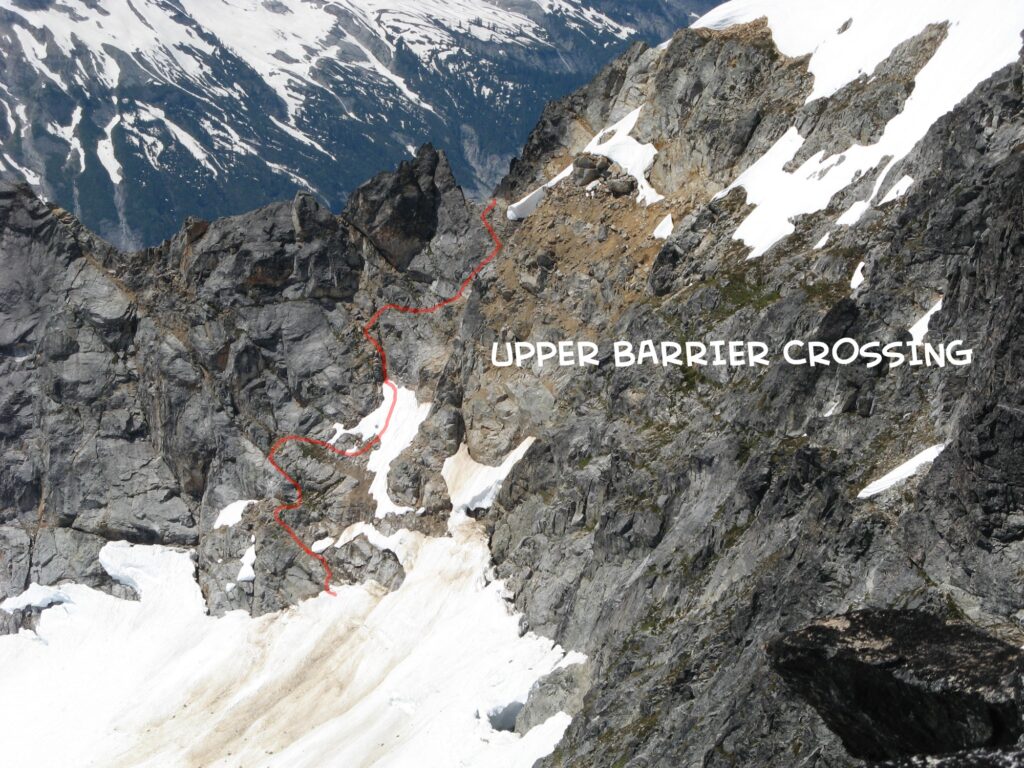

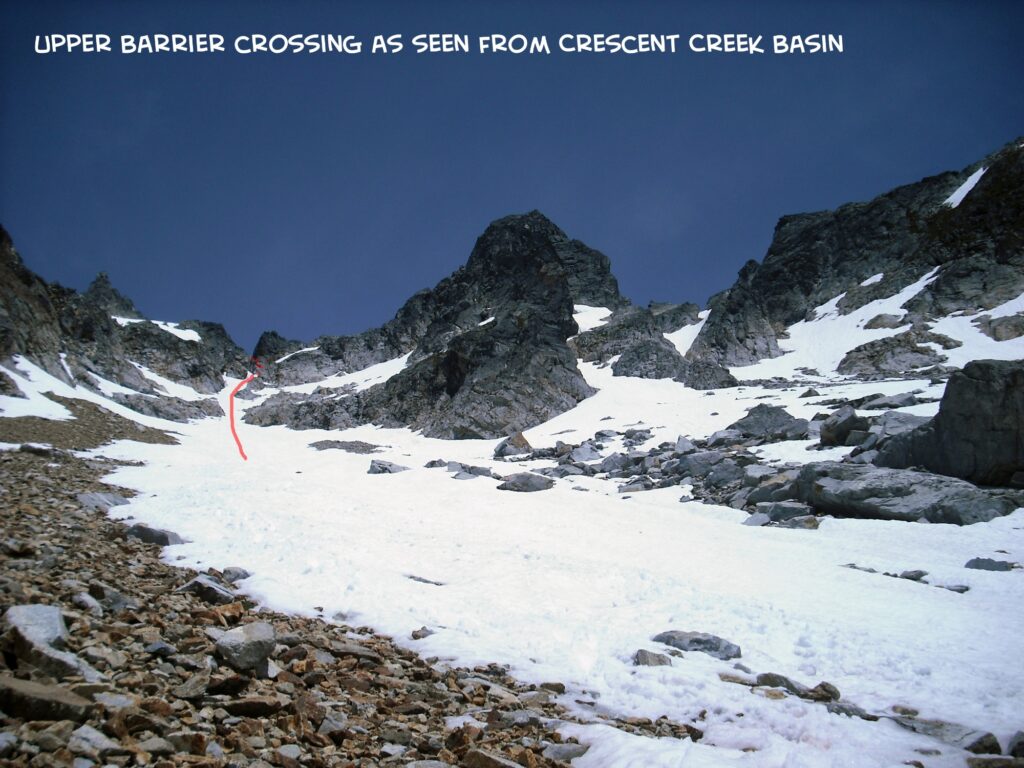

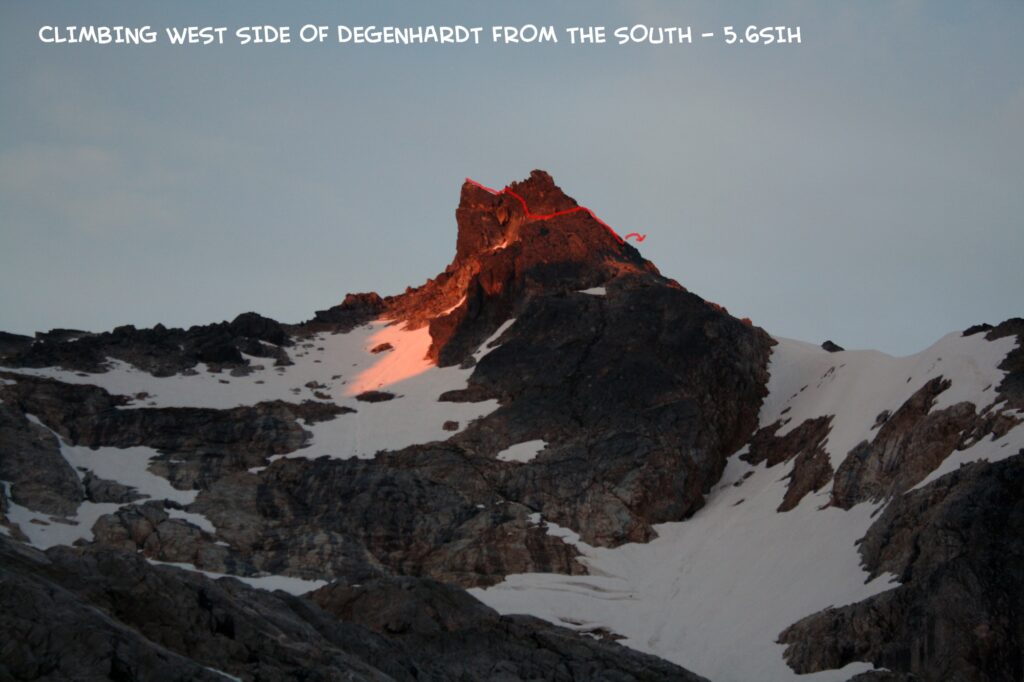

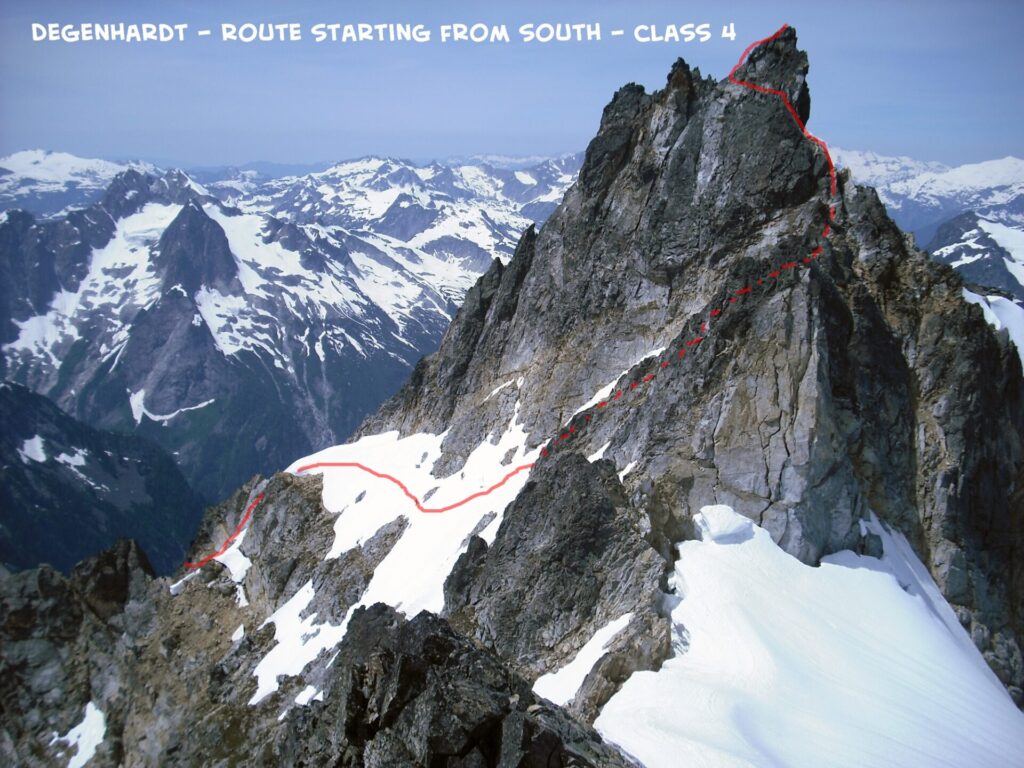

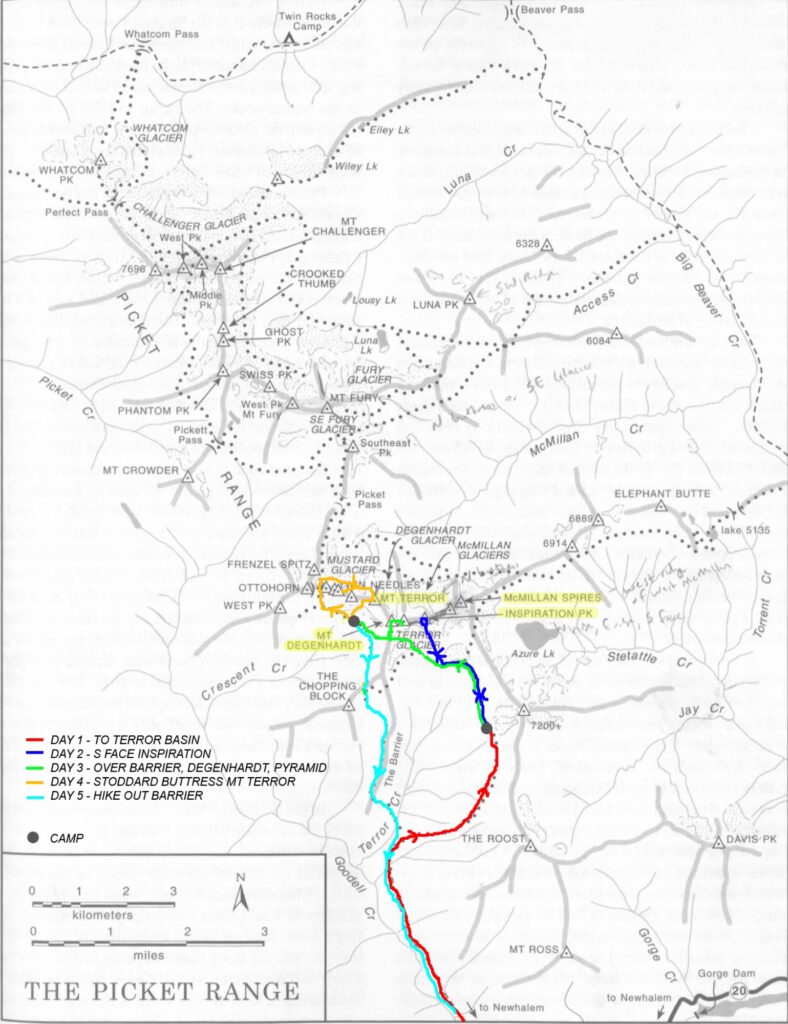

There were four of us in the climbing party: Donn Venema, Jason Schilling, Steve Trent, and me (Steph Abegg). All of us are experienced climbers, and have made several previous excursions into the rugged Picket Range. The first three days of our 6-day trip had been wildly successful, during which we had climbed the South Face of Inspiration, West McMillan Spire, Degenhardt, and The Pyramid. On Day 4 we started off on our last major climb of our trip: the Stoddard Buttress on the north side of Mt. Terror. (We had planned on climbing Wild Hair Crack and Frenzelspitz on Day 5, but now we doubted this would happen given a forecast for a weather system moving in July 6.) The Stoddard Buttress is one of the longest and most committing classic lines in the Pickets, and we were excited for the climb.

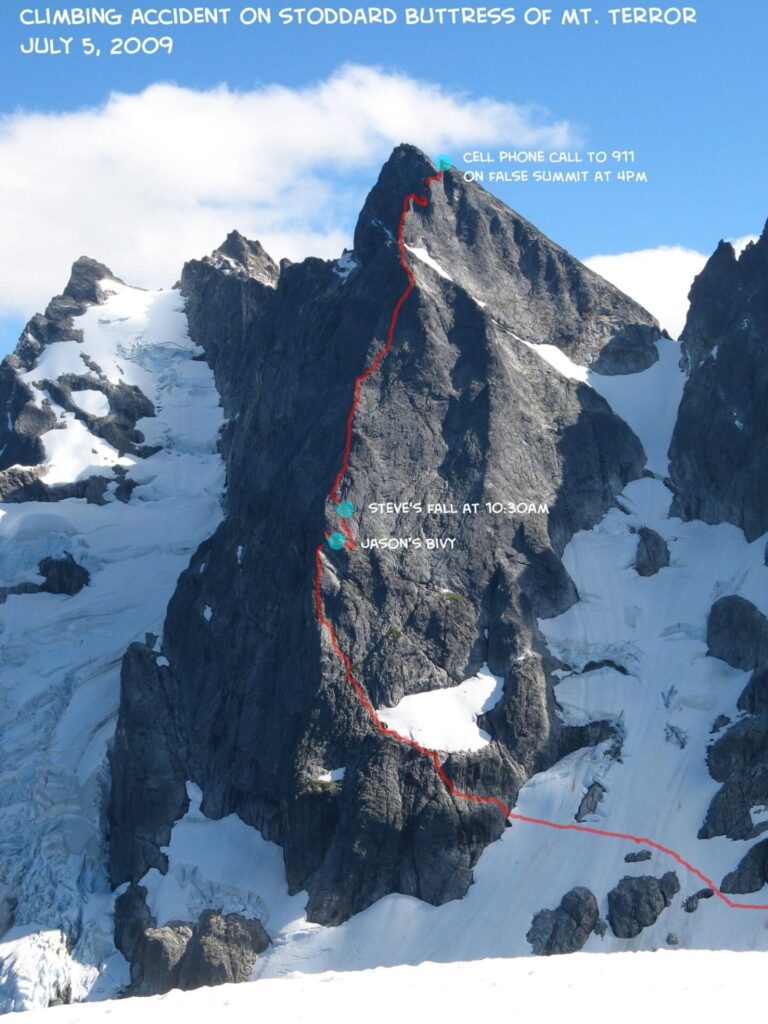

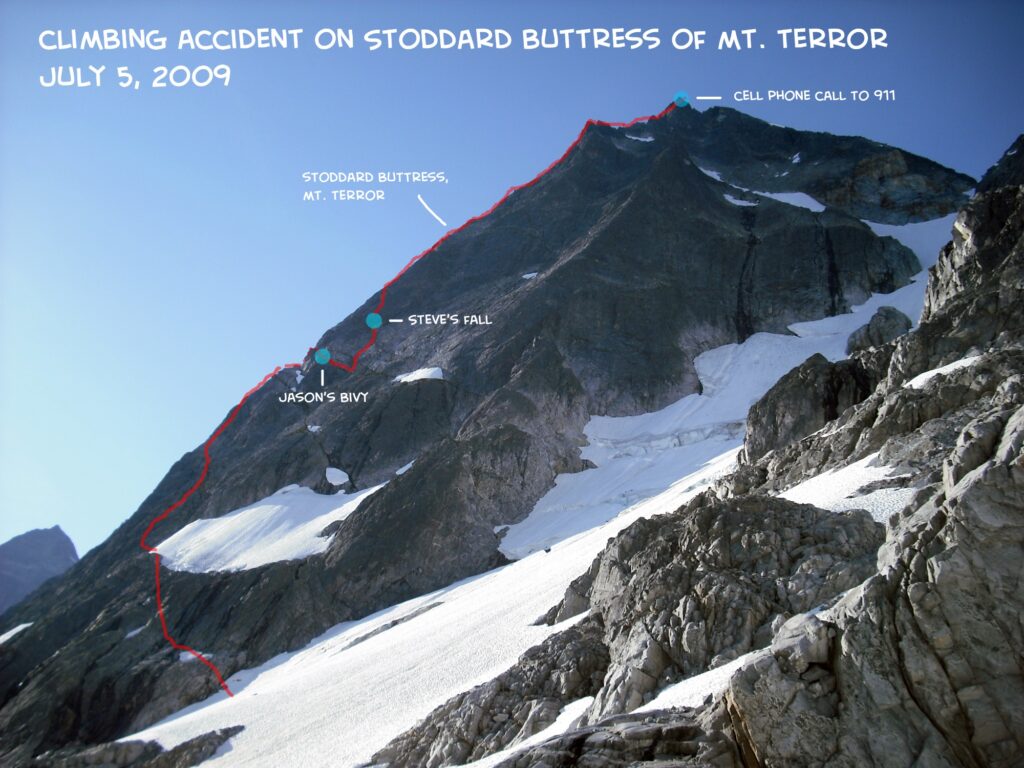

We left our camp in Crescent Creek at dawn, traversed through the Ottohorn-Himmelhorn col, and reached the base of Mt. Terror at around 8am. It was not long before we began simulclimbing up the buttress, taking a relaxed pace to enjoy what promised to be a sunny and warm summer day in the Pickets. Donn and Jason formed one rope team, and Steve and I formed the other rope team. Steve and I were the leading team.

The accident occurred at 10:30am, shortly after we had traversed around a sharp prow about 1/3 of the way up the route. Steve and I had switched leads, and Steve was leading the way up low fifth class ledges back onto the buttress crest. I had just left the belay and begun simulclimbing when I heard a yell above me. I looked up. I think the first thing I saw was a climbing shoe flying through the air. Then, I saw the giant rock and Steve silhouetted against the sky. The next thing I knew I was jerked upwards as Steve hit the end of the rope. He had fallen about 60 feet. Unhurt and surprised, I immediately began calling out to Steve asking him if he was okay. He did not answer me. He was hanging head down at the end of the rope, and I was shocked to see quite a bit of blood running down the rock. I yelled to Donn and Jason below. They heard me and began to climb up towards us.

I was able to lower Steve to a ledge and climb up to him. I noticed that the rope attached to Steve was frayed to the core. I was afraid of the potential for the rope to break or slip loose at any time, so I set up additional anchors on some nearby horns. I then maneuvered over to Steve and somehow flipped him so that his head was up. He was still unresponsive, but moaning. His left leg was clearly fractured and he had lost quite a bit of blood from a head wound.

Donn and Jason reached our precarious perch about 15 minutes after the fall. They anchored in and helped to situate Steve to a better position on the small ledge. With his head now fully upright, Steve began to drift in and out of consciousness. Of the three of us, Jason had the strongest first aid skills, and he stepped up to the challenge, taking control of addressing Steve's injuries. Under Jason's calm directions, we bandaged Steve's head wound and created a makeshift split for his left leg using the aluminum stay from Donn's pack. Steve began to shiver and display signs of shock, so we layered him with our extra coats. We were encouraged by the fact that Steve tried to help put his arms into the sleeves as we told him what we were doing. He began to be responsive enough to complain of the pain in his leg, and asked repeatedly what had happened.

We had brought along a cell phone to try to call friends and family from the summit. Now, dealing with a serious accident on one of the most rugged spots in the state, this cell phone would be our life-line. On the previous days, we had been able to get cell service from the summits of both Inspiration and Degenhardt. We agreed that the quickest way to make a call for help would be to continue climbing the buttress to the summit of Terror. We formed a plan. Jason would stay with Steve. Donn and I would continue up towards the summit as quickly (and safely) as we could and try to initiate a helicopter rescue before the night set in. Making the phone call in time was crucial, as Steve's chances of survival would decrease if he had to spend the night on the mountain, especially considering that the deteriorating weather forecast for the coming days.

Donn and I left the accident scene at 12pm to simulcimb the rest of the Stoddard buttress to the false summit. When we passed the location of Steve's fall, we saw a large dihedral-shaped fresh gash. It is likely Steve had been standing on this section when a sizable chunk of what had appeared to be solid rock tore loose below him. He just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. And being on one of the longest and remote routes in one of the most rugged areas of the Cascades is not somewhere you want to be hurt. Even something as minor as a broken arm could be fatal in the Pickets.

As Donn and I simulclimbed towards the summit, we checked repeatedly for cell phone service, but to no avail. When we reached the false summit, we were discouraged that we still could not find a signal. It looked as if we would have to take precious time and climb to the true summit and make one last effort at finding a signal. Then, in a final effort before continuing upwards, Donn found a signal on the far south end of the false summit. At 4pm, we established contact with 911 and initiated a rescue operation out of Marblemount. It is scary to realize how critical this call was to getting Jason and Steve off of the mountain alive.

By the time we started down the west ridge an hour later, we could hear a chopper flying in the vicinity of the north buttress. The chopper would have to make several fly-bys of the buttress to locate the injured party, to test wind speeds and gauge overhead clearance, and to survey the terrain on which to land the rescue personnel. Once this was done, the chopper would land in Crescent Creek Basin, attach a rescue personnel to a long line, and fly above the north buttress to literally pluck Steve from the mountain. This specialized technique - known as the "short haul" - is a tricky maneuver that requires a lot of skill by the chopper's pilot, and had only recently been added to the certifications of the local rescue team. The windy conditions made the maneuver even more difficult, but pilot Tony Reese was up to the challenge.

At 8:30pm, Steve was successfully plucked from the route. Donn and I cheered when we saw Steve on the end of the line flying high above Crescent Creek Basin on his way to the drop-off point in Newhalem. From Newhalem, a Lifeflight chopper took him to Bellingham. Steve was treated for a femur fracture, broken heel, and deep scalp laceration. He would be out of climbing commission for the season, but otherwise was quite lucky given the circumstances. We were all were relieved when we were informed of Steve's stable condition.

By the time Steve was successfully transferred to Newhalem on July 5, dusk had set in and it was too late to airlift Jason off of the mountain. Jason was unhurt, but was not prepared to descend or ascend the route alone, especially not in the dark. When the helicopter had plucked Steve from the rock face, they had dropped off a bivy supply and several days worth of food and water for Jason. They also left him with a radio. Donn and I had also been given a radio during the brief staging in Crescent Creek Basin, so we could keep abreast with the proceedings and even communicate with Jason. The plan was to airlift Jason off the mountain early the next morning. It was difficult to sleep that night knowing Jason was still high up on Mt. Terror.

However, rain and winds and thick clouds moved into the Pickets during the night of July 5. This made it impossible for the helicopter to safely airlift Jason off of the route on July 6 as had been planned. Donn and I remembered a overhanging ledge system about 200 ft below Jason's exposed position on the mountain, where there was a sloping cave. Via our radio we were able to encourage Jason to make an attempt to descend to this spot. This was a risky undertaking given Jason's scant amount of gear and the now treacherous conditions at his location, but the cave would provide significantly more protection from the elements. Realizing this, Jason made the attempt to move to the ledge below. The radio was silent for an agonizing couple of hours, and our hearts lifted when Jason's voice relayed that he had reached the cave. Jason bravely stated that this was a place he felt he could stay for several days if necessary.

Unfortunately, throughout the day on July 6, the weather continued to deteriorate, and via radio Jason reported that it had began to snow outside his cave high on the mountain. Always looking at the positive side of things, Jason commented that the change from rain to snow stopped the flow of water that was pooling in the cave. However, the snow made even a ground rescue (by Donn and me or a Search and Rescue team) quite hazardous. Feeling as though we were abandoning our friend Jason but realizing that we would be better positioned with the team we were communicating with via radio in Marblemount, Donn and I hiked out of Crescent Creek basin.

Donn and I spent much of July 7 (Jason's 3rd day on Mt. Terror) discussing the situation with the rescue team located in Marblemount. The team was led by Kelly Bush. After skillfully and quickly getting Steve off the wall and on his way to medical help, they immediately began addressing how to get back up there for Jason. A stretch of bad weather turned that process into an extended ordeal, and it was both educational and impressive to watch. Kelly had to constantly watch the weather, evaluate Jason's situation and condition, and always be assessing other options and evaluating risk. Moreover, Donn and I never felt shut out of the process. Donn stepped up to the challenge of communicating with the rescue team while I mostly sat back and listened, occasionally contributing photos I had taken of the accident scene and the route around Jason's location. Given the weather and conditions and Kelly's "minimum risk" mentality, it was decided that our best option was to try to wait for a window to airlift Jason off of the route. It looked as if a high pressure system would move in on July 9. If the weather window did not arrive within a few days, then we would move to Plan B of staging a ground operation. We hoped Jason could stay dry and warm in his sloping cave.

During his bivy, Jason maintained high spirits. He reported that the shortbread cookies in the bivy supply were a hit. He probably wished the supply had included a bottle of burbon and a book as well. Or, better yet, a rap cord and a Hilti. But, joking aside, having the bivy gear was a lifesaver. Equally important to Jason's survival was his character during the entire event. During the rescue planning, everything revolved around the urgency to get Jason back down on the ground, and another person might have made that task harder and forced earlier, possibly riskier action. He found a way to physically make himself at least tolerably comfortable, psychologically resigned himself to the fact that he had to stay there for possibly several days, and was just simply a totally tough dude. His radio calls, indicating that he was doing okay and was still in good spirits, I know gave Kelly just a bit of breathing room as she assessed her options, and certainly reduced the stress levels of all of the rest of us who were hovering around anxiously awaiting for his rescue. At 9:30am on July 9, after spending 4 nights on Mt. Terror, the clouds lifted enough for the rescue team to move in and airlift Jason from the mountain. "How is Steve?" were the first words out of Jason's mouth when he stepped off the helicopter. Assured that Steve was doing fine, "Anyone got something to eat other than a granola bar?"

Fortunately, this was a rescue operation with a happy ending. There are a lot of factors that contributed to the success of this climbing rescue. It is scary to realize how vital some of the decisions were to our survival. For one, having 4 members in our party allowed one of us to stay with Steve (who likely would have died on the mountain if alone) while the other two safely climbed to get help. Secondly, having a cell phone and being able to get service from the summit was crucial to airlifting Steve off of the mountain and getting the bivy supply to Jason before the bad weather moved in. Thirdly, the cave kept Jason relatively warm and dry during several days of cold and wet weather high on the mountain, and without it he very well could have succumbed to the harsh elements. Fourthly, the caliber on the members of our team played a big role in the success of the ordeal. We all kept calm and realized our various roles from the time Steve fell to the time Jason was airlifted off of the mountain. And, perhaps most importantly, the success of the rescue operation ultimately depended on the full-time dedication of Kelly Bush and her rescue team in Marblemount. Looking back, Kelly's skillful decisions were right every step of the way, and the rescue operation was both educational and impressive to watch. This team demonstrated how a rescue should be done.

And as for Steve, he's already got tattooed on his cast a daily reminder of his 2-month goal: "Climb North Twin Sister, Sept 5, 2009". Knowing Steve, he will do it.

UPDATE #1: Jason later wrote an article for the 2010 Northwest Mountaineering Journal, titled "Four Nights at the Terror Hilton," detailing his experience during his 4 nights stranded on Mt. Terror.

UPDATE #2: In March 2012, climbing ranger Kevork Arackellian received the Valor Award and helicopter pilot Tony Reece received the Citizen’s Award for Bravery from Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar in Washington DC. This was for their efforts in the Mt. Terror rescue in 2009. Well deserved! Here's an article about it. The Yakima Herald newspaper carried a captivating front page story shortly after this to document the details of the rescue.